Note, July 24, 2025: Footage of the band playing at Another Place Sandwich Shop in 1993 has surfaced on YouTube, with Sean as frontman and Scott Featherstone on drums. They play Coyote and Klark Kent from the album, as well as a bunch of other wild bluesy jams. Don’t miss the moment at around 19:30 where Sean channels Holger Czukay and starts playing pan flute. More footage may be on the way; watch this space.

In case you missed it in October, the Weston and Steve Good demos are on my YouTube channel. Feel free to check out my other post on Evergreen or leave a comment.

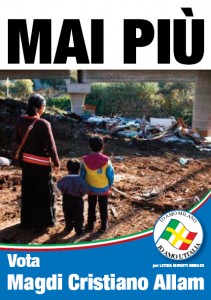

Evergreen’s self-titled, and only, record finally got its due with a reissue in 2005 on Temporary Residence. That release appended two tracks from a low-fi single on Hi-Ball released in 1994, which along with a bunch of tape compilations documented Louisville’s wild mid-nineties house party scene, which launched, among others, Will Oldham’s Palace Brothers and lesser-known acts like the Quiz. The record proper, released in 1996, was recorded by James Murphy, more in print recently for selling out Madison Square Gardens with LCD Soundsystem.

What little writing that is out there on the band focuses on the fact that frontman Sean McLoughlin was a party animal, which is true, but he was also a bit of a poet in his own right, an avid reader of Bukowski, Nietzsche and Burroughs who introduced a bunch of Louisvillians to Fellini via repeated screenings of Satyricon at his rented house out Seventh Street Road near Dixie Highway, his Ford Fairlane parked in the driveway.

The band went through several line-up and name changes, made more confusing by a recent reunion of an early and lesser line-up. They started as a metal band called Revenant, morphed into a popular all-ages funk-hardcore act and ended up as one of guitarist Tim Ruth’s musique concrète projects. (NB: The all-ages act released a retrospective in 2009, Wholeness of the Soul, which lately has sounded pretty good to these ears, and which honestly might be getting more airtime at Premesso in the 2020s that Britt’s Evergreen.) But none of those are the band that made this record.

From about 1994 to 1998, the band was doing something unique, trying to merge roots punk ‘n’ roll à la Stooges with post-rock à la Krautrock. They’d play, à la Can, all night in the woods. Flyers advised the audience to bring a sleeping bag. Britt Walford melded Jaki Liebezeit-like endurance with southern punk rock defiance: at a 1995 Battle of the Bands in Southern Indiana, the power was cut, but Walford kept on playing until two cops picked him up by his armpits and hauled him off, his legs and arms still twitching like some kind of metronymic insect.

But just like McLoughlin was more than a wild man, Walford was more than the drummer. He was responsible for taking the band in a different direction and developing their later sound. All the good bands in those days, up to Nirvana, wanted to record with Steve Albini or his rapidly-budding protégé, Bob Weston, especially Louisville bands (Crain, Rodan), but I’m not sure if Evergreen benefited from their signature stripped-down sound. They had already recorded a lot of four- and eight-track demos, usually with local engineer and musician Steve Good, who knew their sound well. Their summer 1995 Bob Weston sessions don’t sound that different than their Steve Good eight-track sessions. If anything Evergreen gives stronger performances on the Steve Good sessions.

Walford understood this. The rumor was (corroborated on some long-dead web-page of Murphy’s) that Atlantic Records, on Murphy’s tip-off, had paid for the Weston demos and wasn’t releasing them since the band wasn’t signing. But a listen to the band’s 1996 record suggests otherwise. Instead of Weston’s bare-bones engineering, it evokes early disco more than early punk, with a bouncy low end propelled by Walford’s drumming and bassist Troy Cox’s subtle, funk-informed lines. McLoughlin, far from being a punk screamer, occasionally even hits a melody that disappears into a miasma of sound, such as in the last 40 seconds or so of “Solar Song.”

The Weston version of the same song doesn’t even come close, which isn’t to impugn Weston, who recorded some of the best rock records from this period. To compare:

The band was a formidable force that summer. They played house parties and no-name Kentucky clubs with raucous locals like the Auditory Clang and the Quiz. But seeing the band perform at Chicago’s Lounge Ax after they’d been mixing at Albini’s, which was then spread across three floors of the engineer’s house, in summer 1995 was electrifying.

Like contemporaries the Jesus Lizard, the band was a controlled contrast to frontman McLoughlin’s wild antics. Ruth played a Travis Bean borrowed from Albini and the harmonics on “Glass Highway” sparkled over the tight and syncopated rhythm laid down by Walford and Cox, clad in a qiana shirt. Steve Good’s recording best captures the dynamic control the band laid down that night. Listen as McLoughlin’s delivery of cryptically bleak lyrics steadily becomes more insistent, resolving in a repeated, one-syllable shout. Audio defects in the original.

For show-closer “Pants Off” one of the Louisville contingent stormed the stage and, true to the song’s name, took off his pants and jumped on McLoughlin, who whipped him with the mic chord. The two ended up in a homoerotic tangle, the singer still grunting “roly-poly roly poly! Pants off again! roller coaster roller coaster eyeball head!” as the band bashed on. [Thanks to JDD, who was there, for the lyrical correction.]

Evergreen had a rock and roll spirit forged in the conservative and Baptist city of their birth that was hard to imitate. Later bands on the dance-punk bandwagon would find it impossible to measure up to the intensity and originality of their live show and sound. This is a band that not only wouldn’t, but can’t, do a reunion-album-tour. They weren’t actors playing out a recital. They existed at a particular moment in time that not everyone made it out of all right, and for better or worse, it’s gone.

What’s left is the record. Listen to it. They made it because they knew they wouldn’t last forever.

Live at the Cherokee Blues Club, 1995