Recent events — or the media imagery thereof — put in my mind an old Thomas Pynchon article, “Is It O.K. To Be A Luddite?” from nearly forty years ago. There’s a photo that could go with this, but it’s far too obvious, so you’ll have to settle for Kong. For readers interested in the continuing re-evaluation of the Enlightenment, I would draw your attention to the third quote. But I’d paraphrase further by saying that turning to the hulk means denying the machine, which means a chance for the earthly ones to take part in the transcendent.

There is a long folk history of this figure, the Badass. He is usually male, and while sometimes earning the quizzical tolerance of women, is almost universally admired by men for two basic virtues: he is Bad, and he is Big. Bad meaning not morally evil, necessarily, more like able to work mischief on a large scale. What is important here is the amplifying of scale, the multiplication of effect.

[…]

What gave King Ludd his special Bad charisma, took him from local hero to nationwide public enemy, was that he went up against these amplified, multiplied, more than human opponents and prevailed. When times are hard, and we feel at the mercy of forces many times more powerful, don’t we, in seeking some equalizer, turn, if only in imagination, in wish, to the Badass – the djinn, the golem, the hulk, the superhero – who will resist what otherwise would overwhelm us?

[…]

The Methodist movement and the American Great Awakening were only two sectors on a broad front of resistance to the Age of Reason, a front which included Radicalism and Freemasonry as well as Luddites and the Gothic novel. Each in its way expressed the same profound unwillingness to give up elements of faith, however ”irrational,” to an emerging technopolitical order that might or might not know what it was doing.

[…]

To insist on the miraculous is to deny to the machine at least some of its claims on us, to assert the limited wish that living things, earthly and otherwise, may on occasion become Bad and Big enough to take part in transcendent doings.

—

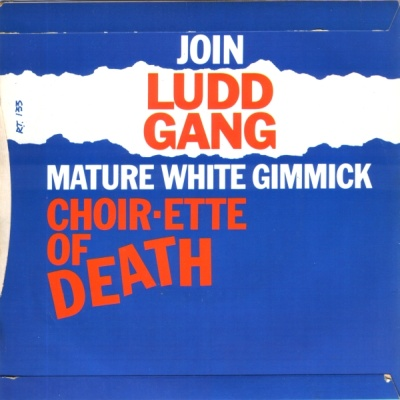

The Fall had a song about Ned Ludd, too, called “Ludd Gang,” a b-side to “The Man Whose Head Expanded” from their wonderful 1983 two-drummer period. I wonder what Mark E. Smith would think of the current contest in America. “Ludd Gang” has a little dig on Gang of Four which MES explained in a 1981 interview in SPEX Magazine.

S: Why don’t you like the Gang of Four?

Mark: Because their songs are about politics. They preach the leftist ideas. They went to University and belong to the privileged class. The problem is that they pretend to know what the working class wants. But they haven’t got a clue. Sham 69 however knew what they were talking about and they were good. The English working class (including myself) find the music of the Gang of Four offensive, insulting, hurtful. I listed to their first singles a lot in those days. Later on I saw them live, too and then you could tell they lacked the feeling when they got to the heart of the matter. I mean, how could they talk about problems and changes in the world when they play like that. Maybe I am being cynical but it’s more important to me to be honest to myself. I don’t like the music of the Gang of Four. I prefer rock’n’roll bands.

Finally, I’ll point out a Gang of Four song that’s also topical and leave it at that.