April’s poetry discovery was that Polish poet Zbigniew Herbert has not only a poem, but an entire volume entitled Rovigo, with the eponymous poem being indeed about that small town in Veneto midway between mythical Venice and sumptuous Bologna where I lived in 2007 and 2008. (Sadly the book is available only in German at Amazon, and only at the exorbitant price of $66.)

April’s poetry discovery was that Polish poet Zbigniew Herbert has not only a poem, but an entire volume entitled Rovigo, with the eponymous poem being indeed about that small town in Veneto midway between mythical Venice and sumptuous Bologna where I lived in 2007 and 2008. (Sadly the book is available only in German at Amazon, and only at the exorbitant price of $66.)

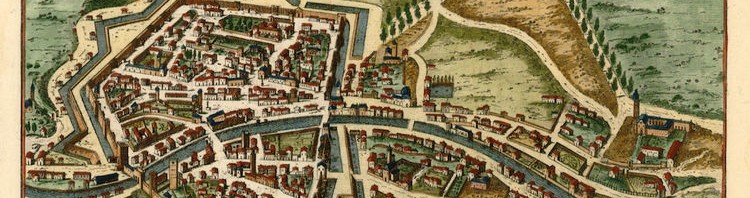

I didn’t mean to live in Rovigo. I had bigger and better plans — I was going to work in Milan, or Rome, or teach in Bologna, or at least do a fellowship in Modena. My girlfriend lived in Rovigo, but she wasn’t really from there, either — her family was from closer to Verona, and she’d grown up out on the Po Delta, and gone to school in Bologna, where we’d met. I’d gone there once or twice, to meet her mom and have lunch, and hiked along what I remembered as a humid canal path smelling faintly, not unpleasantly, of vegetation, to get back to that train station with its two windows, with yellowed photos of Piazza Vittorio Emanuele and la Chiesa di Santa Maria del Soccorso taped up, to go back to Bologna, which had trains going to Milan and Switzerland, not to the provincial destination of Chioggia and Adria.

I finished a master’s in 2007 and got to Rovigo in the infernal heat of Ferragosto, when no sane southern European works. But possibly I would not be working either: back home, financial TV personality Jim Cramer was bellowing at the Fed to “open the discount window.” The subprime crisis was happening. I wasn’t going to find a job in Milan, or Rome, or anywhere. Anywhere other than Oxford School, Rovigo branch. My temporary stopover ended up being slightly more permanent. And then, I got married. My train wasn’t going anywhere. Rovigo became my reality. I stayed a year. I go back indefinitely. I just got back, actually.

So I can agree quite well with Herbert that Rovigo is “a city of blood and stone like others/a city where a man died yesterday someone went mad someone coughed hopelessly all night.” It is, doubtlessly, a real city quite apart from the myths of nearby Venice and the feasts, architectural, gastronomic and otherwise, of Bologna. Professor Adam Zagajewski, himself no stranger to the Veneto, has more on this in an excellent essay.

There are a couple of translations going around the internet and I will post the one by Alissa Valles I found on Professor Zagajewski’s site here — I don’t read Polish, but the English-reader in me finds the unattributed translation on PoemHunter.com severely lacking. There’s a world of difference between the mechanistic “nth time” and the more intuitive, indubitably casual “umpteenth”, and “filled with love” is no comparison to “throes of passion.” And what about the gashed mountain nearby, “like an Easter Ham surrounded by kale” versus “like a holiday cut of meat draped in sprigs of parsley”? I’m less sure about that. Easter ham taps into that most sacred of Catholic holidays, celebrated with great vigor in both Poland and Italy. I’ll let the reader judge by linking to the anonymous translation above and pasting Valles’ below. As a side note, I wonder if Herbert’s gashed mountain is one of the nearby Colli Euganei?

Zagajewski’s essay in an excellent little study on how the foreigner — especially the educated and sensible one — experiences Italy:

[W]e’re only interested in those who died five hundred years ago. We’re not coming here to be reminded of the triviality of life, we’re not coming here to think of Berlusconi or Prodi, or of the reform of the health care system; we come here for the beauty alone.

But by the end of the poem,

the non-visitable city of Rovigo changes its color. […] He just mentions, nearing the poem’s closure, “arrivi—partenze,” keeping the Italian words in the text, and we understand what he means: arrivi—partenze, birth and death, beginning and end.

In the poem, Rovigo has become real, a real place in Italy where people come and go, are born and die. There’s a lot to unpack here in terms of the reality of life in small-town Europe in 2014: the Rovigo of today is, for many who work in more developed Padova or Ferrara, a bedroom community with cheaper rents and better eldercare for parents. For many recent immigrants, the neighborhoods around the train station are a cheap place to live while they go ply their trades in the bigger cities of Mestre, Padova or Venice. (Including, but not limited to, the world’s oldest profession.) As economic terms concentrate greater wealth and more features of a completely developed economy to internationalized mega-cities (of which Milan is the prime Italian, but not an especially good, example), Rodigini find themselves commuting more and more, going to work a competitive job in Milan and commuting home on the weekends. The arrivals and departures of Herbert’s poem, written over 20 years ago, back when Italy had more of an economy, are even more stark now.

One detail I will take exception to in Zagajewski’s essay is that Rovigo is a dull or boring town. Small or provincial, yes, quite likely. But it is not over-industrialized (for that the Venice-bound traveler need look no further than neighboring Mestre), and has three very finely preserved piazze — one of them Vittorio Emanuele, the others Piazza Garibaldi and Piazza Roma, known to natives as Piazza Merlin — that would be the envy of a metropolis like Milan, where a piazza is often merely a traffic circle. As my mother-in-law tells me, the Adigetto Canal until the early 1950’s used to run straight through the middle of town, down the Corso del Popolo that is today’s main pedestrian drag, and it doesn’t take much imagination to see Rovigo as a smaller, less-developed Venice.

On a clear day, when there is no winter fog or summer afa — that crushing, grayish humidity that sticks between the Po and Adige Rivers in the summer heat in the lower Veneto — from the right bank of the canal out towards Sant’Apollinare, one can see distant snow-covered peaks of the Monti Berici.

ROVIGO

ROVIGO

Rovigo station. Vague associations. A Goethe play

or something from Byron. I passed through Rovigo

so many times and just now for the umpteenth time

I understood in my inner geography it is a singular

place though it is certainly no match for Florence.

I never put a living foot down there. Rovigo was

always coming closer or receding into distance.

I lived then in the throes of a passion for Altichiero

of the San Giorgio Oratorium in Padua and also

for Ferrara which I love because it reminded me

of the plundered city of my fathers. I lived torn

between the past and the present moment

crucified many times by time and by place

But nonetheless happy with a powerful faith

that the sacrifice would not be made in vain

Rovigo was not marked by anything in particular

it was a masterpiece of averageness straight roads

ugly houses—depending on the train’s direction

just before or just after the city a mountain suddenly

rose up from a plain cut across by a red stone quarry

like a holiday cut of meat draped in sprigs of parsley

apart from that nothing to please hurt catch the eye

But it was after all a city of blood and stone like others

a city where a man died yesterday someone went mad

someone coughed hopelessly all night

AMID WHAT BELLS DO YOU APPEAR ROVIGO

Reduced to its station to a comma a crossed-out letter

nothing just the station—arrivi—partenze

and that is why I think of you Rovigo Rovigo